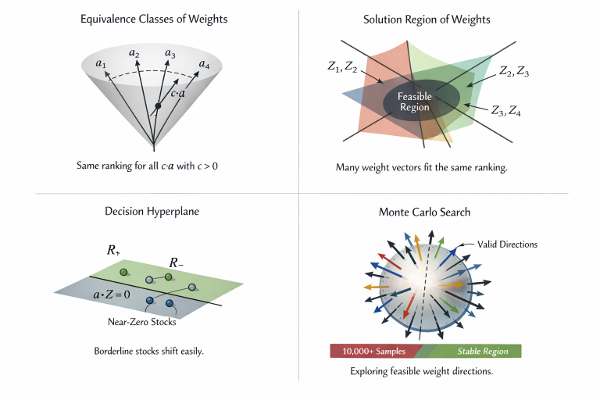

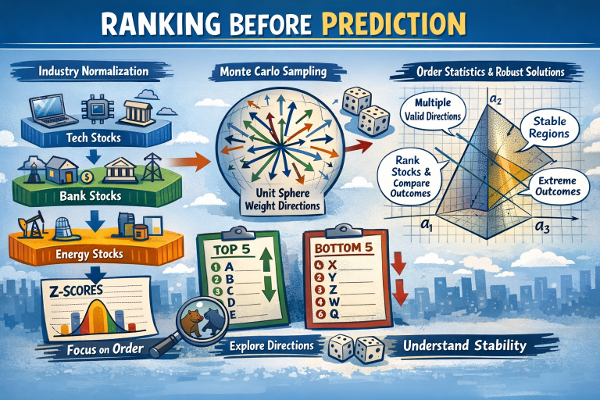

Consider three stocks, each described by two standardized factors:

Z_PE (cheapness; lower is better)

Z_EPSG (earnings growth; higher is better)

Let their factor vectors be:

Stock A: a = (1, 1)

Stock B: b = (-1, 1)

Stock C: c = (0, 1), Z_PE is zero, means e.g. PE right on sample average, its z-score is zero. But really it is not important.

Assume a linear scoring rule: s(z) = x1 * Z_PE + x2 * Z_EPSG

The scores are:

s(A) = x1 + x2

s(B) = -x1 + x2

s(C) = x2

Notice the identity: s(C) = (s(A) + s(B)) / 2

This holds for all real x1, x2.

As a result, some orderings are impossible. For example, there is no choice of (x1, x2) such that: s(A) > s(B) > s(C)

This is not a numerical accident. It is a geometric constraint.

This small example captures, in its simplest form, a phenomenon that reappears at scale in real factor models.

Please read the full note 4 in PDF