This is the third note in a series on quantamental stock rankings. The

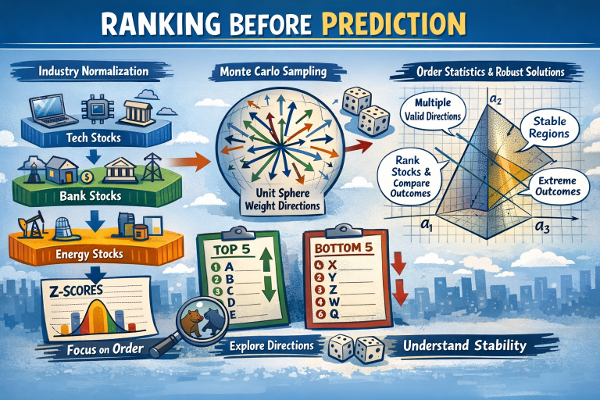

first note

(Ranking Before Prediction) and the second one was

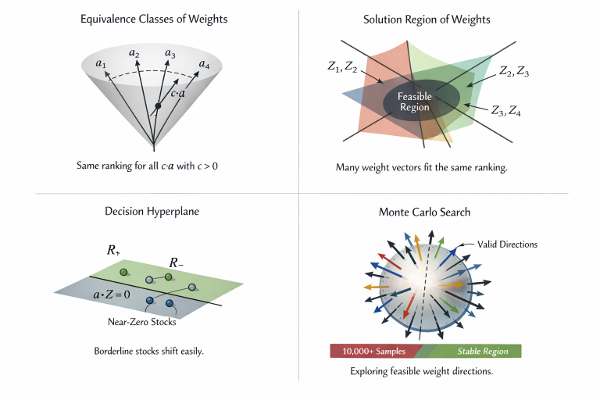

(Why

Learning Factor Weights Is an Ill-Posed Inverse Problem)

In quantitative equity research, we rank stocks.

In large language models, we rank tokens.

At first glance, these activities seem unrelated. One deals with financial

markets, the other with text. One operates on quarterly or monthly

horizons, the other on milliseconds. And yet, once you strip away

domain-specific language, the core operation in both systems is the

same:

Given a large discrete universe and incomplete

information, construct an ordering and act on the top of

it.

Prediction is often presented as the central task. In practice, selection

is.

In equities, we rarely need a precise return forecast for every stock.

What matters is which stocks end up near the top of the list. In

language models, the system does not need to know the “correct” next

word. It produces a ranked distribution and selects from it.

This blog explores why ranking-based systems arise naturally across

domains, why early language models looked surprisingly similar to

factor models, and what modern language models changed—not in the

objective, but in where structure lives ...

Please read the full note in pdf